Linguistic Relativity

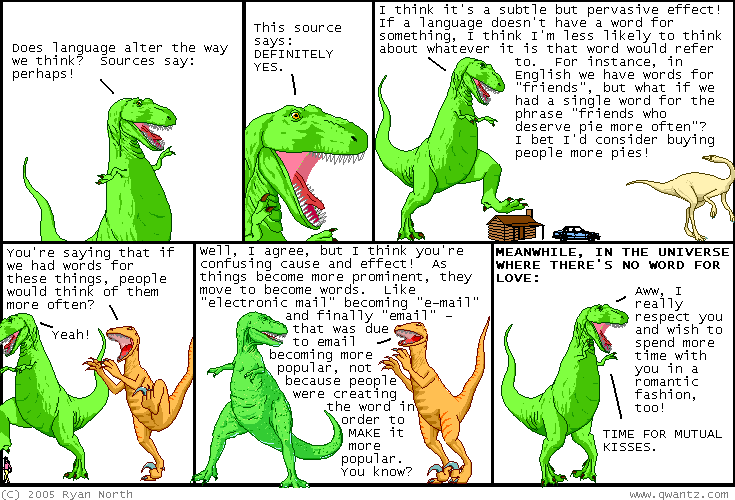

Linguistic relativity, also called the “Sapir-Whorf hypothesis”, is the principle that claims that language and thought influence each other in a dual, cyclical nature.

The two forms are classified as:

- Deterministic (strong)

- Relative (weak)

This hypothesis was first discussed by 19th century thinkers like Wilhelm von Humboldt who saw language as the spirit of a nation (nationalism was becoming a fixture in Europe at the time). Later on, early 20th century thinkers headed by Franz Boas adopted the idea to an extent, although Edward Sapir favoured a more deterministic form. His student, Benjamin Whorf came to be seen as the primary proponent of determinism based on studies he had conducted, and Harry Hoijer, another one of Sapir’s students coined the term “Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.”

While linguists generally agree that relativism can be shown to be true to some extent, there are many criticisms of the determinism. Among the criticisms of deterministic Whorfianism are:

- One of Whorf’s central arguments was that the Hopi terminology for time gave them a unique understanding of the workings of time, different from the typical Western conception of time. Pinker argues that Whorf had never actually met anyone from the Hopi tribe and that a later anthropologist discovered, in fact, the Hopi conception of time was not so different as he claimed.

- The problem of translatability: if each language had a completely distinct reality encoded within it, how could works be translated accurately and precisely? Yet, literary works, manuals, etc are regularly translated. Effective inter-language communication thus negates, or at the least, weakens Whorf’s argument.

See also:

- Culture, Language and Personality by Edward Sapir

- Language in Mind by Dedre Gentner, Susan Goldin-Meadow

- The Language Hoax by John H. McWhorter

- The Language Instinct by Steven Pinker